Global Patent Filings Down: What Does It Mean?

WIPO reported the first drop in international filings in 14 years. Here's what it means

The World Intellectual Property Organization announced in its annual review that global patent applications fell for the first time in 14 years. WIPO is saying that it is “too early to draw conclusions” but already practitioners are sounding the alarm; WIPO itself called the drop “concerning.” The headline in Reuters was “innovation falters.” Although the drop was not dramatic at 1.8%, it is always worth paying attention to applications; obviously, they are the leading indicator for issued patents, which itself is a leading indicator for innovative new products entering the market.

Moving beyond the headlines, though, what does this mean for global innovation, and why is this happening? Are there any clues that practitioners can use to get the most out of 2024? This week in Nonobvious, we will review what this report might mean for the year ahead and evaluate some of the potential causes of the decrease in filings.

An Innovation Bottleneck? Maybe, or Macroeconomics

Although this news has generated a lot of headlines, its meaning is slightly different than it may appear in the news. WIPO’s report specifically addressed the number of PCT applications. That is different than the total number of global patent applications in national jurisdictions. This report, therefore, is best thought of as describing international filings, not total global filings.

WIPO does collect the total number of international applications, but that number is in its World Intellectual Property Indicators report, or WIPI, and we will not get that information until later this year. The 2023 WIPI, which covers 2022 filings, called the global patent filings a “record high” and the third consecutive year of growth of 1.7%. Notably, patent filings are becoming more globalized. China’s patent filings have grown to reach nearly half of all national filings and are growing faster than the US or Europe. And patent offices in the so-called Global South, most notably India, Indonesia, and South Africa, as well as others like Saudi Arabia, grew even more quickly last year. That said, there were already some clouds on the horizon. Trademark applications fell and WIPO Director General Daren Tang said last year that “uncertainty continues to weigh on the global innovation ecosystem,” foreshadowing the potential for a drop in patent applications as well. There has been a perception as well that science is becoming less disruptive over time; could that be trickling down to patents?

Globally, Tan is correct. The number of patent applications has increased at a compound average growth rate of 3.9% since 1990, but it has been far from a straight line. There were significant global decreased in 1991, 2002, and 2009, each of which corresponds to years of massive global economic convulsions—specifically, meaningful recessions in the United States. It is interesting that the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis did not significantly affect global patent applications despite its large impact on Asian economies; this reflects how little Asian economies contributed to innovation at that time. It is worth noting, however, that the fall in applications does not appear to be highly correlated with historical interest rates, at least in the United States; interest rates fell in all of those time periods. This correlation with recessions decreases the likelihood that there is a general innovation glut and more that patenting and R&D budgets are susceptible to general belt-tightening.

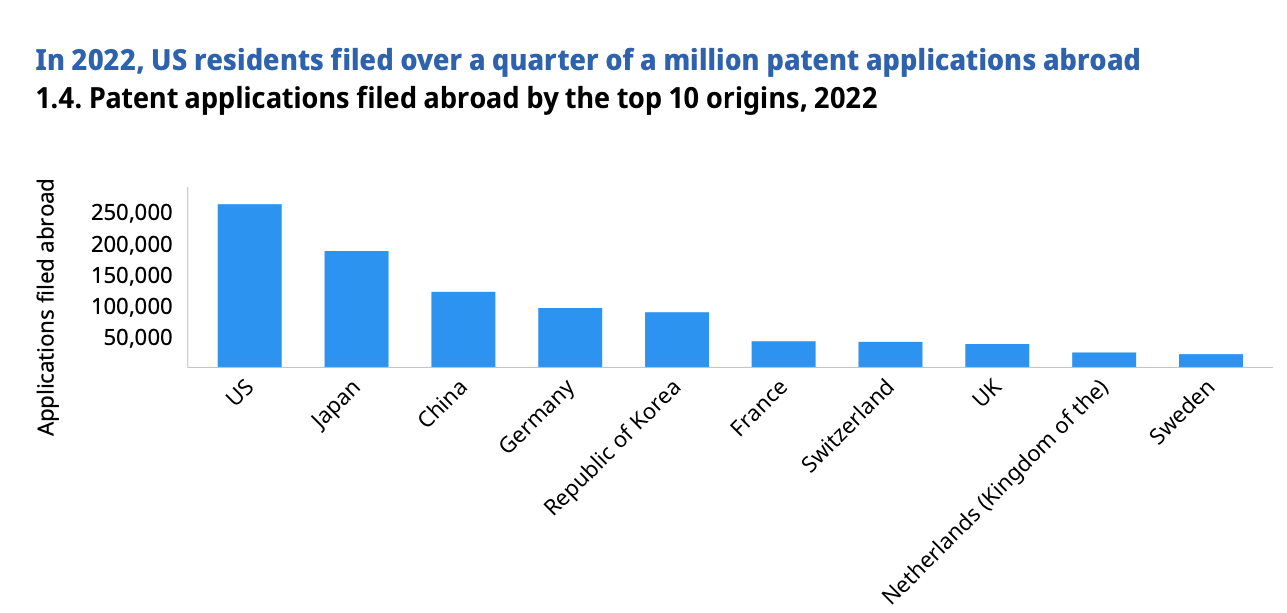

The decrease in PCTs is likely driven by the United States. While China now produces 46% of all patent applications, they do not file internationally nearly as often. American inventors filed abroad nearly twice as often as Chinese inventors do, and Japanese inventors filed nearly 50% more international applications. The decrease in PCT may therefore be reflective of a decrease in US applications that has not yet been reported. The number of issued patents has decreased for four straight years, though in 2022 the number of applications has recovered from a COVID-induced decrease. In other words, rather than interest rates, it seems that applications are more sensitive hard macroeconomics.

Applicants may also be shifting towards quality. The number of applications per GDP tells a very different story. Chinese filings per GDP are very high, but the quality is considered to be low, per this study from UC Berkeley. Patent filings per GDP in innovation economics may be reflective of industry mix (for example, South Korea’s economy is largely microelectronics based, while the US is the global center of software) but also quality (if you invented a core patent, you may not need to file more). So while the decrease likely reflects macroeconomic factors in the US and China, it may not be all negative.

Patent practitioners are already seeing the impacts of budget pressures. This suggests that there may be more pain up ahead as macroeconomic pressures increase on patent activity overall. But as conditions improve over the next 12 months, perhaps the second half of 2024 will be brighter leading to a 2025 that is up as a whole. Historically, drops don’t last that long.

Weekly Novelties

Amazon and Huawei signed a massive global patent licensing agreement over 5G patents (Reuters)

PUMA lost a design patent case against Rihanna’s FENTY brand (Hypebeast)

The Federal Circuit held oral arguments in Celanese v. ITC on a fascinating question: did the AIA change the on-sale bar for trade secret protected inventions? (Patently-O)

A lawyer argues that automotive companies are wasting millions of dollars on fees for patents they should allow to lapse (IP Watchdog)

An argument against proposed European SEP laws, saying they would create an “SEP monster” (Juve)

A Ford patent application was published for reconfigurable seats; electric vehicles do not have large engines, which opens up the possibilities of larger indoor cabins and previously-unusual configurations (Motor Authority)

Bank of America increased its patent portfolio by 70% in five years (Cision)