Guest Post: It's Time to Amend the Patent Act for AI Inventors

As AI inventorship hopes dim, Jeffrey Ostrow argues that we should amend the Patent Act to revive the concept

Below is our first-ever guest post by Jeffrey Ostrow, formerly of Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP. If you want to submit a guest post to be published in Nonobvious, reach out and we will consider your article.

The US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has dedicated countless hours to an increasingly urgent task: determining how much human involvement is necessary to qualify as an "inventor" under patent law. The agency’s focus is understandable, but the rapid pace of technological advancement means that soon, this will no longer be a matter of nuance or interpretation—it will be a necessity.

Imagine a not-too-distant future where artificial intelligence (AI) systems develop a new compound that could cure cancer, and no human can be fairly identified as the inventor. What happens next?

Under current patent law, the answer is simple but troubling: if no human can be listed as the inventor, no one owns the patent. This presents a significant problem. In the absence of clear ownership, no company or individual will spend the enormous amounts of money necessary to test, refine, and bring this groundbreaking treatment to market. The result? Potentially life-saving innovations could languish in the dustbin of history, unused and forgotten.

The root of the present ownership issue lies in an outdated legal framework. The Patent Act, as it stands, requires an "inventor" to be human—which makes sense if we assume that only humans can invent. But today, AI systems are already contributing to cutting-edge advancements in fields as diverse as drug discovery, materials science, and cybersecurity. And tomorrow, those same AI systems could make discoveries entirely on their own. When they do, our laws will be unprepared to handle the implications.

This is not a hypothetical scenario; it is an immediate reality. If we don't act now, we risk stifling innovation precisely at the moment when AI has the potential to transform entire industries and solve some of humanity's most pressing problems.

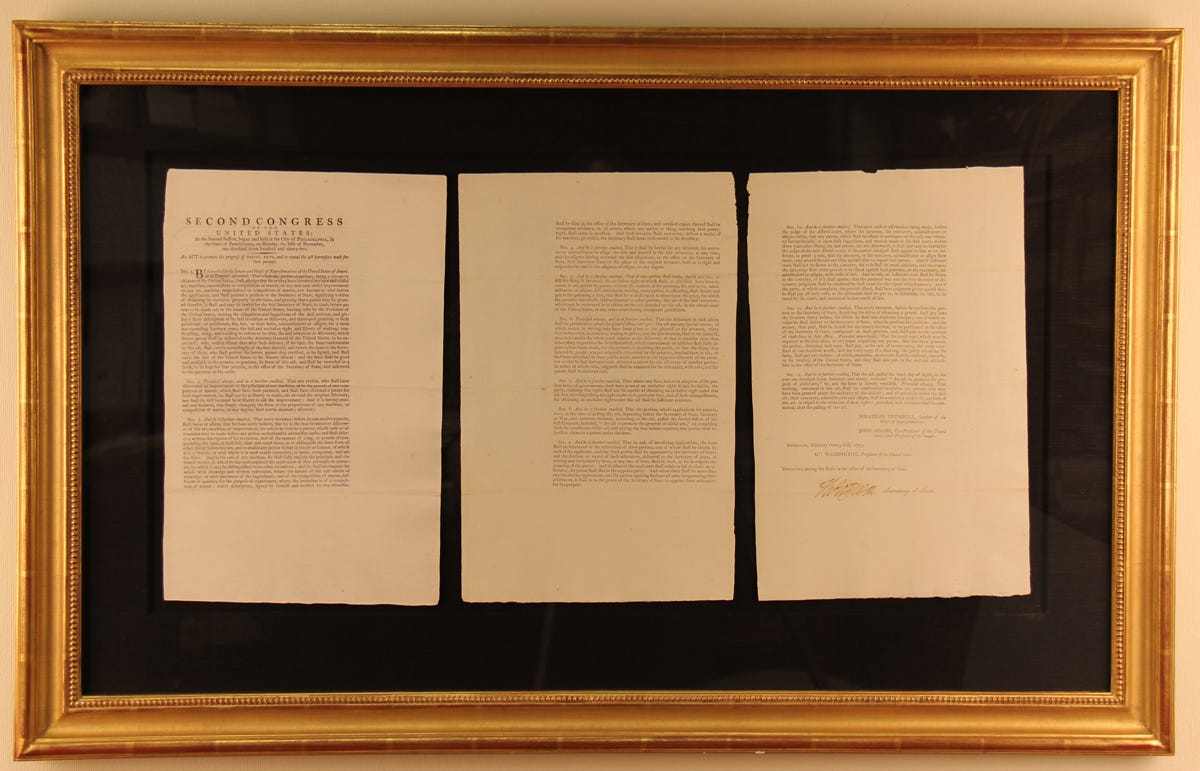

The Constitution grants Congress the power to promote the "progress of science and useful arts" by securing for limited times the exclusive rights of inventors. For obvious reasons - it was 1787 after all - nowhere does it say that those inventors must be human. In fact, as Justice Sandra Day O’Connor famously noted in the Feist v. Rural Telephone Service Co. 499 US 340, 349 (1991) case (often referred to as the "White Pages" case), the “primary objective” of Article I, Section 8 is not to reward creators for their own sake but "[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts." Indeed, the patent system exists in part to encourage innovation and ensure that society benefits from it. Motivation is just one goal - and a very good one. But the other is much bigger and recognizes the clause’s primary objective that is broader and benefits us all: “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.” At the end of the day we have to ask: what does society get? The answer to this question is our lodestar.

There is nothing in the foundational text of our patent law that prevents us from recognizing non-human creators. The Constitution itself is flexible enough to allow Congress to adapt the law to meet the needs of a changing world, just as O'Connor emphasized in the context of copyright law.

Critics will argue that allowing non-human inventors will create a host of legal and ethical challenges. Who would own the patent—the AI itself? Its developers? The company that trained the algorithm? These are valid questions, but they are questions we can address through thoughtful legislation.

Thankfully, there are signs that at least some in Congress are paying attention to issues with our patent system. Already, there are two recent Senate initiatives tackling other perceived shortcomings in the patent system, the Promoting and Respecting Economically Vital American Innovation Leadership (PREVAIL) Act and the Patent Eligibility Restoration Act (PERA). These bills have both shown serious potential to pass Congress, which signals momentum for meaningful reform in crucial areas. Congress must add AI inventorship to that list to ensure that our laws are forward-thinking enough to embrace the future, rather than clinging to the past.

The clear Congressional impetus to pass legislation, like the PREVAIL and PERA, should trigger broader discussions that go beyond a single political moment. While no one has all the answers, comprehensive hearings would allow a diverse range of stakeholders—small inventors, large corporations, academic researchers, and legal experts—to highlight their respective views. Thanks to the DABUS series of cases, this crucial issue is being handled by the courts based on what the law is today. What we need to do instead is discuss what should be.

As to my view: we must amend the Patent Act to reflect the reality of AI-driven innovation. Congress can get this done in a thoughtful, non-partisan way. Otherwise, we risk standing idly by as life-saving inventions go undeveloped simply because our legal system couldn’t keep pace with the technology that created them. The ultimate goal of the patent system is to serve the public good. Let’s make sure it does.

Jeffrey E. Ostrow is the former Chair of the Intellectual Property Department at Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP. He currently consults on strategic IP issues companies face and teaches at Berkeley Law School, where he developed a class called the “Business of IP” which examines how intellectual property issues increasingly shape and drive real world decision making.

Prior Art

Last year, I covered and explained the fight between Scarlett Johansson and OpenAI over a voice product that she alleged sounded eerily similar to her character in the movie Her. (Although she claimed to have retained lawyers, no case was ever filed.) In the article, I observed that copyright seems like a less-clear example for entertainment applications than likeness and trademark. Johansson now seems to be the poster child for AI issues for Hollywood. This week, a viral AI-generated video went public of “celebrities” wearing obscene t-shirts in protest of Kanye West’s Nazi t-shirt website. Though she approved of the message, Johansson called for federal AI likeness legislation. This is a fight that is not going away. Now, I don’t think that anyone is going to think that this is real, or that the founders of Google and Facebook sat down for this video. But you could imagine a much more believable video, especially now that AI video generation is getting so good.

Weekly Novelties

Vaishali Udupa, the commissioner of patents for USPTO, resigned (IAM-Media)

The Federal Circuit upheld the PTAB’s IPR authority over expired patents. See Apple Inc. v. Gesture Tech. Partners, LLC, 2025 WL 299939, *2 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 27, 2025) (link)

USPTO issued clarifications for its new IDS fee schedule. In short, submissions in reexamination proceedings are exempt from IDS size fees while filing benefit claims in a reissue will result in new continuing application fees (JD Supra)

In gambling news, a lawsuit between two roulette companies, Evolution and Light & Wonder, came to an end as the roulette patents were held to pertain to abstract ideas. Game patents are not illegal per se, but typically relate to technical aspects; game mechanics are very gray post-Alice (Next.io)

The European Commission withdrew its controversial SEP legislation, saying that there was “no foreseable agreement” to be reached. However, it left the door open to pursuing different legislation in the future (JUVE Patent)

Relatedly, the European Commission also dropped legislation to regulate AI that would have allowed consumers to sue over fault or omission of an AI provider (Reuters)

Trina Solar sued Canadian Solar over patents relating to tunnel oxide passivated contact cells, pursuing $147m in damages (PV Magazine)