More than you ever wanted to know about CPC codes

Plus! A new patent bar, a washing machine with an ironing board, and a semiconductor lawsuit between US-China national champions

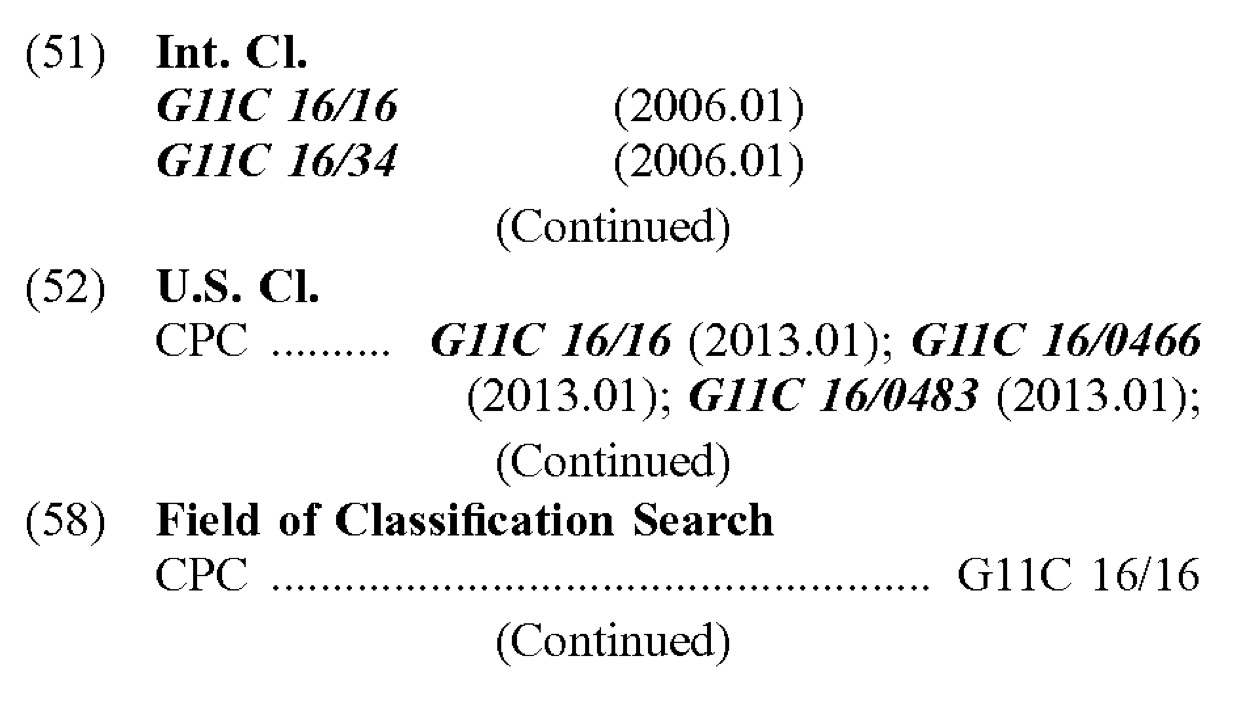

When you look at the cover sheet of a patent, whether you’re an inventor looking at your first patent or a seasoned attorney looking at patents all day, you have likely seen this small section of the cover sheet:

These are the codes that the patent office uses to organize patents, called CPC codes. Even practitioners do not often think about how CPC codes are created. But in this week’s Nonobvious, we’re going to learn more about CPC codes than perhaps you ever wanted to learn.

How CPC and IPC codes work

USPTO has maintained a history of patent classification. Patents have always been classified, but it was only in 1830 that USPTO began to seriously classify patents with sixteen formal categories. Soon after, in 1836, the New Patent Act turned that into a formal requirement. The requirements proliferated and by 1878, USPTO had 158 requirements. Other countries, like Germany and Britain, started adding their own patent classification services. In 1900, USPTO turned its classification scheme into the US Patent Classification scheme, or USPC, while in 1970 Europe harmonized into the European Classification, or ECLA, system. That said, the number of codes and standards proliferated.

Today, there are two main patent classification systems. The first is the International Patent Classification system, or IPC, which is promulgated by the World Intellectual Property Organization under the Strasbourg Agreement. The second is the Cooperative Patent Classification system, or CPC, which is a US-EU collaboration that started in 2010 and launched in 2013. Although the US still used USPC codes alongside USPC codes for a while, as of 2021, USPTO is now fully on the CPC system, as is the EU. These codes are based on concepts and organize patents that have similar features or elements. They are not assigned with any consideration given to any probable amendments.

If you want to read a CPC code, think of it as a coded tree. A code looks like A08D 203/02 (though in Europe they don’t use any spaces). The first letter is the CPC section, like Human Necessities or Physics; these directly correspond to the IPC sections (other than “Y,” which is a catch-all section for something so novel it does not belong anywhere). Next is a two-digit class, followed by a one-letter subclass. Lastly, there is a group or subgroup. If it is in the main group, the number behind the “/” will always be “00”; if there is a relevant subgroup, it will be another number. There are over 250,000 CPC codes. The IPC codes are structured the same way. These codes are extremely specific, and although there is a rough correspondence with the IPC there is not perfect concordance. For example, CPC code G02C 1/04, which is “Bridge or browbar secured to or integral with partial rims, e.g. with partially-flexible rim for holding lens,” is essentially identical to the IPC code of the same number, while G02C 2202/02, which is “Mislocation tolerant lenses or lens systems,” has no direct IPC twin at all. The full concordance table is available on the official CPC website.

Codes are assigned to patents immediately upon submission by the patent office—USPTO contracts this out to Serco, Inc, though examiners will re-do the classification once the patent is granted; the EPO is similar. The exact methodology is a secret, though it is known that the main preclassification work is done primarily using the claims and the abstract. These codes serve two primary functions. The first use is the traditional one: searching for prior art. While practitioners are typically limited to things like keyword or semantic searches, USPTO has the advantage of assigning a CPC code and looking at all of the prior art within a CPC code that may not use the expected keywords. This is one of the ways that they find prior art that practitioners find surprising during the prosecution process. Practitioners can search by CPC code too, but they have to use a keyword search to guess which CPC codes are relevant, which is a laborious task. The other main use for assigning a patent examiner within an art unit. USPTO assigns several CPC codes to a patent, not just one, and then applies an algorithm to determine which examiner has the most experience with the mix of CPC codes assigned to a patent. If there is a tie, it is broken by the workload of the examiners at hand, so even if you could perfectly predict your CPC codes, you could not perfectly predict which examiner you would get.

CPC codes may seem arcane, but they are designed to not be so sparse as to have only 1-2 patents in them. Mastering them can help you with your prior art searches, and you can even search by CPC codes. The great thing about CPC codes is that they are based around concepts, not keywords, so they can capture art that you might not have found by conventional means.

Weekly Novelties

Notable news items

USPTO has created a new patent bar specific to design patents (Law360)

An argument in favor of patent buyouts in biotech (Stat News)

Patently-O meditates on AI inventorship and patent law (Patently-O)

Latter-day litigation

TwinStrand Biosciences v. Guardant Health Inc, U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware, No. 1:21-cv-01126: Guardant Health loses an $83.4 million infringement case; the strategic implications are more serious, and Guardant’s stock slid 7%

Yangtze Memory Technologies Company, Ltd. v. Micron Technology, Inc., Northern District of California, 5:23-cv-05792-VKD: YMTC, one of China’s semiconductor champions, is suing Micron regarding its 3D NAND gates. Probably unrelated, YMTC is looking to raise fresh funding

Elekta Limited v. Zap Surgical Systems, Case No. 2021-1985 (Fed. Cir. 2023): A Federal Circuit case that, while somewhat limited in scope, should give practitioners pause in being careless with the use of references in IPR reviews; they may be considered relevant art in an obviousness determination

Gripping Gazette entries

US 11814285 B2: A system for multiphase reactions that efficiently separates the outputs of chemical reactions of different phases from the University of California

US 11814780 B2: A washing machine that also has an ironing board on top from Haier. For those who don’t like how much space ironing boards take up

US 11817232 B2: An Air Force patent for carbon nanotube interconnects, which are resistant to strain and highly conductive

Eventful expirations

US 6643913 B2: An interesting method of manufacturing laminated ferrite chip inductors (which are useful because they are very cheap conductors) through holes of “U” shaped connectors.

US 6643911 B2: A more effective method for creating electric motor yokes (the part that sticks out) in a way that does not waste materials

US 6643923 B1: A method from Sony for producing flexible wiring boards, which is particularly useful in many of the new, non-flat electronics popular today