The Legacy of Amazon's 1-Click Checkout Patent

Plus! A major EDTX venue case with TikTok, a sweeping FTC Orange Book action, and a multi-tool for painters

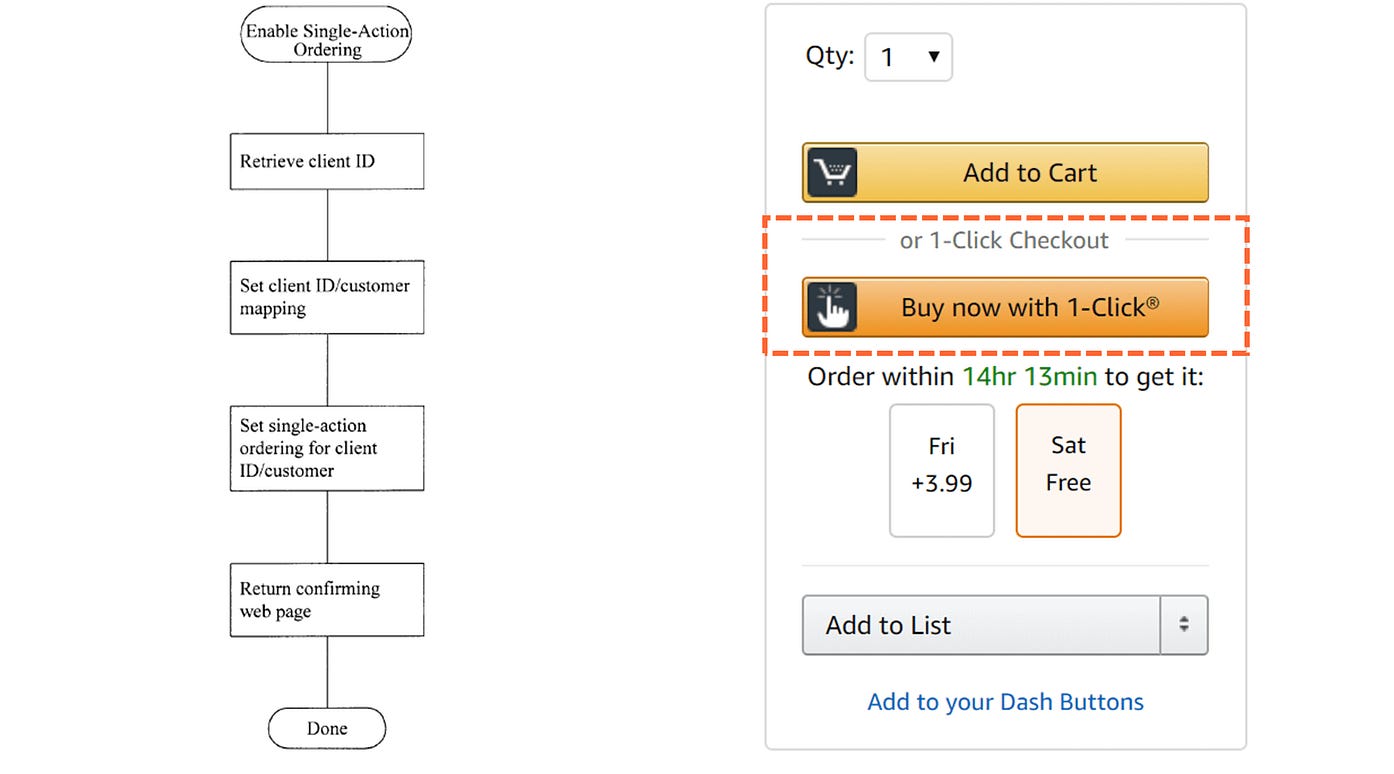

It’s perhaps the Dot-Com era patent: in 1997, Amazon unveiled its 1-Click Checkout feature. Users with Amazon accounts could use their account information to purchase a product with just the press of a button. It was revolutionary for the fledgling online store, helping catapult it to the forefront of online shopping. And no one could copy it thanks to Patent No. US 5960411 A, which was granted in 1999. That’s right: Amazon patented 1-Click Checkout, and it defended that right vigorously. The ‘411 patent was estimated to be worth billions. It gained such notoriety that its expiration even attracted news articles in requiem.

So why did this patent become so notorious? The 1-Click patent was critical for Amazon’s success while also being controversial over the matter of nonobviousness—especially when Amazon fatefully started enforcing it against Barnes and Noble. The outrage was so great that the GNU foundation boycotted Amazon for 3 years while a Stanford history of the patent observed that it helped create a movement against software patents as a whole. The 1-Click patent story is one of how a particularly well-timed patent can make a big difference in a company’s life and shape a whole industry—as long as the patent covers one crucial innovation.

One Click, Many Impacts

One click checkout was an instant a boon for online purchases. One paper found that the introduction of a one-click method boosts sales by a sky-high 28%.1 Even today, a whopping 97% of consumers have abandoned a cart at some point due to lack of convenience. In fact, 18% of shoppers abandon their cart because the checkout process was too complex; imagine how many more did the same in 1997 when 1-Click was first introduced. The feature was met with such fanfare that it was even called out in Amazon’s annual shareholder letter.

Not one month after the ‘411 patent was issued did Amazon sue Barnes and Noble for its Express Lane feature, which offered similar functionality to 1-Click. Powerfully, Amazon was granted its patent in October, so it filed its lawsuit in November, during the holiday season when 19% of all retail sales occur. Amazon sought a preliminary injunction in the District Court for the Western District of Washington, which was quickly granted despite Barnes and Noble arguing the ‘411 patent was invalid. The injunction was granted in December 1999, delivering a crushing blow the very year that e-commerce entered the public consciousness. This was appealed to the Federal Circuit, which ruled in January 2001—over a year later—vacating the preliminary injunction, in part because BN.com modified Express Lane to include a second click. The damage was already done, though, and today Amazon is the world’s top book retailer, reportedly controlling over half of all book sales in the United States.

The BN.com lawsuit generated significant controversy. Some claimed that the ‘411 patent was approved without proper knowledge of the prior art, though it actually survived a USPTO invalidation proceeding (mostly) intact.2 It was one of the first internet patent cases, so it generated significant law review activity, though the standard in Amazon v. Barnes and Noble is relatively similar to the 4-factor test later upheld by the Supreme Court in eBay v. MercExchange (2006). That said, the public blowback was so intense that Jeff Bezos felt compelled and publish an article arguing for changes to software patents, including a 3-year lifespan for software patents and a public comment period for prior art. He also gave an interview claiming that Amazon’s patents were purely defensive. That said, it was difficult to take Bezos’s comments seriously. After all, Amazon’s actions against Barnes and Noble were clearly not defensive, nor was it the only example of Amazon deriving value from its patents. Apple paid Amazon $1 million to license the patent for iTunes and iPhoto.

The 1-Click patent was also essential for building Amazon’s brand and is a lovely demonstration of how patent exclusivity can be used to drive trade name value. Amazon’s brand attributes include ease of use and speed, and the 1-Click feature was a key, customer-facing part of that. Amazon still has a live trademark for 1-Click, meaning that none of its competitors can use that phrase in describing their one-click features (though if push came to shove, that trademark might be a victim of genericide). When the ‘411 patent expired in 2017, half of all Amazon app customers were using 1-Click regularly. It is unlikely that Amazon could have built such brand equity around that term, or associated it so strongly with Amazon, had it not had twenty years of exclusivity to associate its name with that technology. They still rely on that brand name today—when they created the Amazon Go store, Fast Company called it the “physical manifestation Amazon’s 1-Click checkout.” The patent helped Amazon create a brand of convenience.

The expiration of Amazon’s 1-Click patent was also monumental in demonstrating how a patent expiration can have a sizable impact on company formation. Today, it is a key technique used across e-commerce to boost conversion rates. Several of the “fast checkout” companies were formed after 2017. Why is that? That is when the patent expired. In fact, Bolt, the most famous such startup, is the result of a pivot away from a crypto payments startup. Billionaire founder Ryan Breslow has previously explained that he started his pivot directly in response to the expiration of the ‘411 patent, and since then over half a dozen notable companies have started to offer one-click as a service. It is no surprise that other such products, like Apple Pay and ShopPay, were launched afterwards. After all, Amazon had extracted licenses and litigated when it was needed. Why risk awakening the giant in Seattle?

Weekly Novelties

Notable news items

Congress continues to mull over the PREVAIL Act, which would overhaul PTAB in a manner favorable to inventors (IP Watchdog)

The FTC filed challenges to over 100 Orange Book patents and threatened possible further actions against to 10 of the largest pharma companies (Fierce Pharma)

Chinese companies, including Huawei and Tencent, now account for 6 of the top 10 cybersecurity patent holders (Nikkei)

Gripping Gazette entries

US 11809618 B2: An Apple patent for an app to sell clothing that fits the user particularly well, clearly tied in to Apple TV but perhaps also the Vision Pro

US 11808142 B2: A patent from Exxon Mobil for a method of tracing gas as it moves up out of a well using a radioactive tracer

US 11805716 B2: An interesting tilling device that cuts and tunnels in unison

Latter-day litigation

In re: TikTok, Inc., 5th Cir., 23-50575: A huge 5th Circuit case that makes it easier to get out of EDTX (perhaps Samsung will stop sponsoring ice rinks in Marshall, Texas)

HIP, Inc. v. Hormel Foods Corporation, No. 22-1696 (Fed. Cir. 2023): Although this case on valid inventors for a bacon patent was decided in May, the Supreme Court rejected cert this week

Infogation Corporation v. Honda Motor Co. Ltd., 2:23-cv-00513 (E.D. Tex.): InfoGation, a software company, sued Honda over several GPS patents

Eventful expirations

US 6640340 B2: A special swaddling cloth for babies, making it easier to swaddle than trying to tuck a normal blanket 20 different ways

US 6640346 B2: A visor for helmets that, in a twist, is about protecting the helmet while in transport, not the human while wearing the helmet

US 6640369 B1: A tool for painters that includes a paint brush comb, a paint roller scraper, a scraper blade, and a container cover remover—that is, everything but painting itself

This is not a surprising result in the sense that “friction” is generally known to affect checkout rates in e-commerce. What is surprising is how big the effect is; online sales is often a game of doing 20 small things that each improve the outcome by 1-2%, not one big thing that has a 20% impact.

In the EU, however, 1-Click was rejected on nonobviousness grounds. As always, there will be significant differences between what different national offices will permit based on the determinations of their examiners! It’s particularly interesting that the ‘411 patent survived given that the Federal Circuit claimed that prior art by companies like Compuserve created nonobviousness problems for Amazon.

Very good article, Evan. Can I translate part of this article into Spanish, with links to you, and a description of your newsletter and you?