What Can Patents Tell Us About Historical Innovation?

A paper in one of the top journals in economics uses patents to tell us about how innovation has changed over time

How has innovation changed over time? While we started with fire and spears, over time the nature of technology has evolved to include the printing press, paper, fireworks, steam engines, trains, planes, cars, and computers. For those who believe innovation has declined in recent decades, there is an increasing interest in studying what can be done to drive innovation. That requires understanding what has driven progress in the path. Some call this emerging field Progress Studies.

A newer, interesting paper purports to use patents to examine this trend. It not only looks at patents but looks at textual similarity across patents to determine which areas are driving innovation. Furthermore, it also looks at which areas of invention drive technology in other areas and attempt to measure changes in the quality of patents over time. This week in Nonobvious, we are going to dive in to this paper and what it says about the history of technology.

A Changing Mix

The main contribution of this paper is an attempt to create a similarity score of patents to understand how different inventions or categories drive innovation. They do this by breaking up the text of American patents from 1840-2010, and measuring how often a patent mentions unique terms, like “electricity” or “petroleum” rather than “inventor” or “process.” The metric is clever but relatively simple to calculate; it relies on looking at how common a term is in a patent and multiplying that by the inverse of how common that term is across a body of patents. Roughly, the metric is (% of a patent that contains a term)*log(inverse of % of patents that contain a term). However, to look for patents that are influential, they then look backwards, only looking for the number of patents that used the term before the publication of a patent. They then do some matrix math to make the measure slightly more useful.

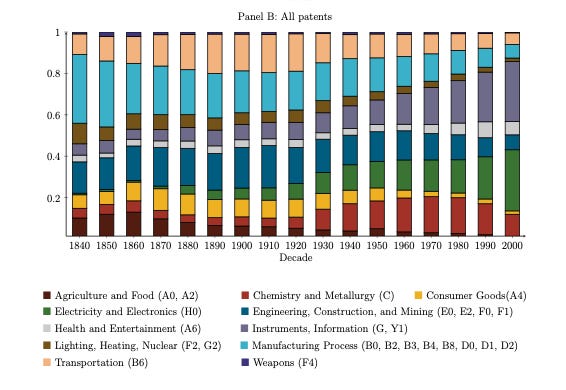

The goal of the paper is to identify the breakthroughs and which areas in which they occurred. They found three main time periods of innovation: electricity in 1870-1880, chemistry and automobiles in 1920-1935, and biotech (especially genetics) and computing from 1985-2010. Perhaps the most interesting finding is that while the composition of breakthrough technologies has changed over time, the composition of patents overall has not. It is quite interesting that some critical patents were filed before the breakthrough periods. The Wright Flyer patent, for example is from before the 1920-1935 innovation; similarly, the Noyce patents are from the 1960s. What is interesting about this observation is that it implies that many breakthrough periods are influenced by a breakthrough that occurred prior to a Cambrian Explosion in a field as a whole, quite often by a decade. Although this measure predicts citations by more than 5 years, which they view as a positive, it is interesting that there is still somewhat of a lag. The authors agree that citations are a good measure of quality; they just are interested in predicting which patents will be cited.

On a meta level, there is a threshold question of whether patents are a good way to measure innovation writ large.

The main argument for this is that historically, of course, patents have been a major part of the story of innovation. And the limited evidence we do have around patents indicates that it improves outcomes for companies, especially startups, that have them. Arguably, then, the more innovative your solution, the higher the incentive to get a patent, which would add to the accuracy of this measurement. And indeed, the quantity of patenting is used to measure innovation in a number of contexts. Consulting companies use patents to measure firm innovation and economists use aggregate-patenting activity to conduct studies on economies. Although there is a known need to account for quality, this is something that researchers are working on. And in any case, patent citations seem to be getting closer to the metal; pure research papers are citing more to patent data and vice versa, according to a recent paper. Add on to that the fact that patents are very legible and well-documented and you have the makings of a good data set.

At the same time, it is pretty clear that patenting is not a perfect measure of innovation. The well-known critique is that not all important innovations are patented. One paper found that of the “R&D 100 Award” only 10% of the winners were patented (though not all R&D necessarily progresses past that stage). Most famously, the eminent historian W.H. Price argued in a 1906 book that patents were not a major factor in the Industrial Revolution for the simple reason that many important inventions of the Industrial Revolution were not patented. There are other potential issues. One paper found that companies tend to not cite their own papers, which could imply that at least some of the innovation that is being patented is not internally driven. Another issue is if there is a bias towards patenting in some fields. This is a known issue, for example, in software, and in the life sciences where subject matter eligibility issues abound after Mayo v. Prometheus. I’ve heard from chemistry practitioners, for example, that many of the best chemistry inventions are protected by trade secret. This means that studies that use patent activity as a measure of innovation may systematically exclude certain industries or regions that specialize in those categories.

Still, it is interesting to see that patenting trends, while not perfect, do provide some signal. The fact that even today patent activity increases in predictable ways in response to key inventions indicates that there is still something worth measuring and that patents will continue to be one way to measure the innovation of economies and industries.

Weekly Novelties

Apple, on the heels of some major losses at the ITC, is stepping up its lobbying efforts (New York Times)

Reddit disclosed a patent complaint from Nokia (Reuters)

The EU put out its annual patent numbers, and despite the global fall, patent filings are up, further suggesting that the decrease may be driven by the US (Yahoo Finance)

Phillips, which is over 130 years old, was one of the top applicants (Philips Newsroom)

The Federal Circuit invalidated a “Tic Tac Fruit” circuit (Bloomberg Law)